If you want to build a website, but don’t want to pay the monthly fees for a hosting service, this is the guide for you.

As most web-servers are lightweight in terms of resource usage, you can use old hardware such as a laptop, or a mini PC like a Raspberry Pi. Or, you can build a VM if you have a hypervisor environment.

I’ll go over how to set up WordPress, a free CRM, which allows you to easily manage the pages of your website and use free templates to build good looking webpages.

Exposing a web-server to the internet can be dangerous if you don’t have the correct security in place. This guide will show you how to configure Cloudflare to proxy and tunnel web traffic, so you don’t need to expose ports to the internet. The free version of Cloudflare also provides some great analytics and extra Web Application Firewall (WAF) services to further protect your server.

Having your web-server proxied by Cloudflare does introduce some issues with WordPress, this guide covers how to fix them safely.

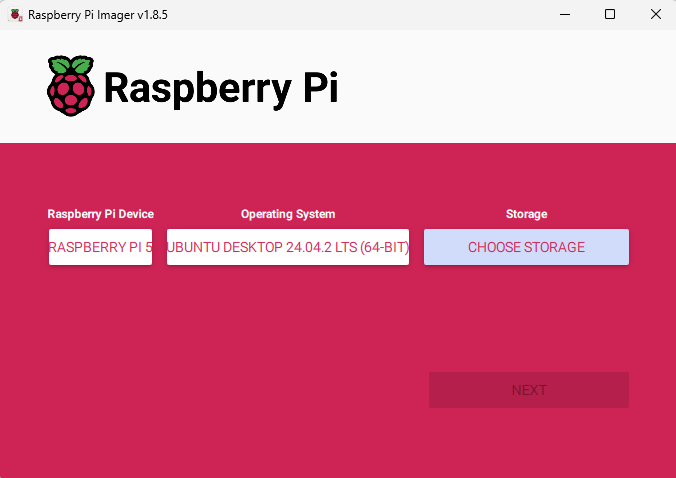

This guide is build for Ubuntu Server 24.04, once you have installed that OS, head to the tutorial:

Tutorial

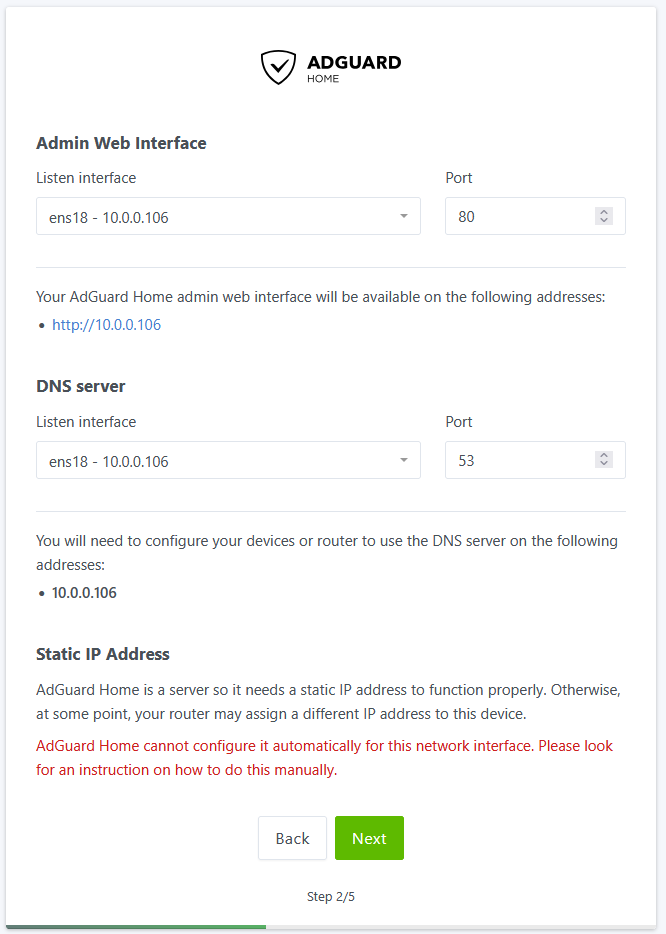

Once you have an Ubuntu Server 24 Operating System ready:

Step 1:

Update your server.

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -yStep 2:

Install Apache2.

sudo apt install apache2Step 3:

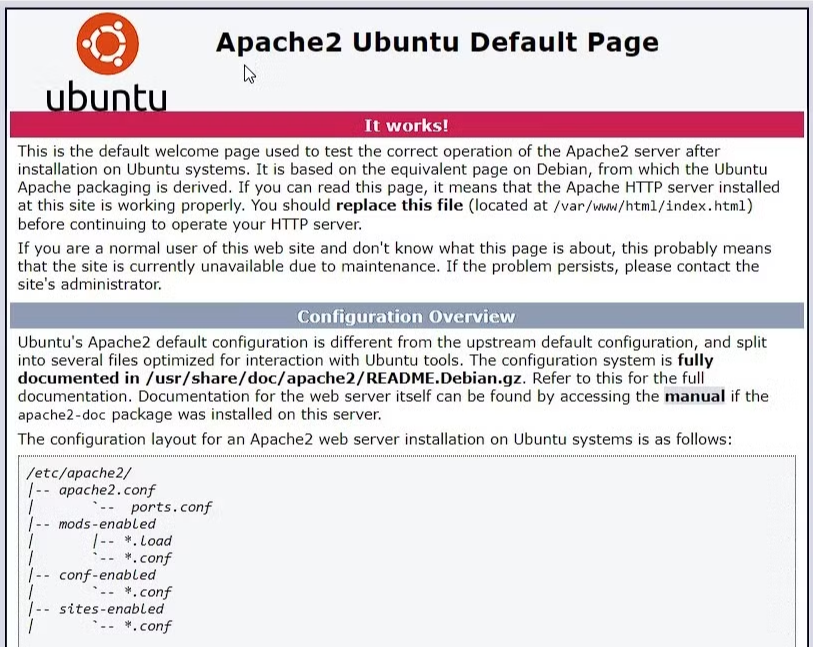

Ensure Apache installed correctly by browsing to the servers IP address, you should see a screen like this:

Step 4:

Install MariaDB, an SQL server.

sudo apt install mariadb-server mariadb-clientRun the secure installation script.

sudo mariadb-secure-installationMariaDB is a fork of MySQL, a database server which will be used by WordPress.

Step 5:

Install the server-side scripting language PHP.

sudo apt install php php-mysqlStep 7:

Open mysql to create a database and user.

sudo mysql -u root -pRun the following commands, remembering the semi-colon at the end, to create a database and user. Replace ‘Database’ with something similar to your domain name, and ‘User’ to whatever username you want. Use a secure password, as this database will control access to your server.

CREATE DATABASE Database;

CREATE USER 'User'@'localhost' IDENTIFIED BY 'Password';

GRANT ALL ON Database.* TO 'User'@'localhost';

FLUSH PRIVILEGES;

EXIT;Step 8:

Now it’s time to download and install WordPress.

Navigate to the website root directory.

cd /var/www/html/Use wget to download the WordPress installation files. If you don’t have wget installed already, install it with sudo apt install wget

sudo wget https://wordpress.org/latest.tar.gzExtract the compressed files.

sudo tar xf latest.tar.gzThis will extract all files to the /var/www/html/wordpress directory. For easy management and less hassle, move the contents into the root directory.

sudo mv /var/www/html/wordpress/* /var/www/html/ && sudo rmdir wordpressEdit the filesystem permissions to make Apache the owner.

sudo chown -R www-data:www-data /var/www/htmlTo install WordPress fully, browse to the IP address of your server. You should see a WordPress installation screen.

Enter the Database name, username and password you created for the mysql database, and run the installation.

Step 9:

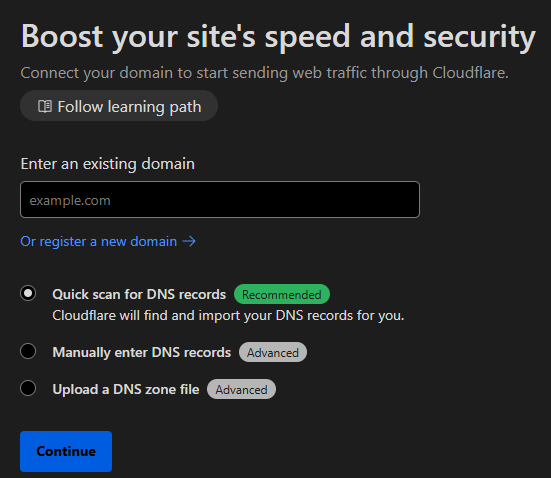

Go to the Cloudflare dashboard https://dash.cloudflare.com/ and make an account if you haven’t already.

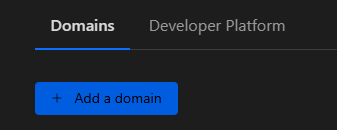

You will need to adopt your domain into Cloudflare, go to ‘Account Home’ and select ‘Add a domain’.

Type in your domain name, and hit ‘Continue’.

From here, Cloudflare will guide you though changing your nameservers, although the process will be different depending on your registrar. Once you make the change, it can take a few hours for it to propagate. In the meantime, navigate to ‘Zero Trust’.

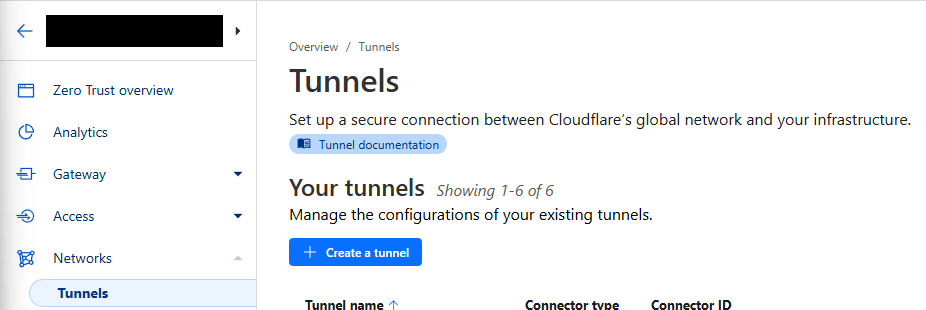

We are now going to set up a Cloudflared tunnel. This will not only allow you to tunnel traffic to your web-server, but also allow you remote access if you wish, using Cloudflare WARP, or the 1.1.1.1 app.

Navigate to ‘Networks’ and select ‘Create a tunnel’.

Select ‘Cloudflared’ as the tunnel type’.

Give your tunnel a name, and hit next.

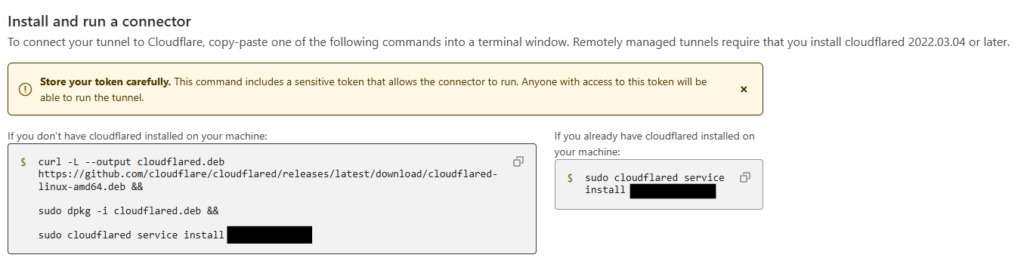

Select the ‘Debian’ environment, with your CPU architecture.

Copy the left hand box into you server terminal, and wait for the connector to appear in the bottom box.

Once it appears in there, hit next to add a route. If you want remote access into your network, set this as the network subnet using CIDR notation, such as 192.168.1.0/24.

If you only want traffic for your web-server to be routed down this tunnel, set the route to the IP address of you server with a /32 notation.

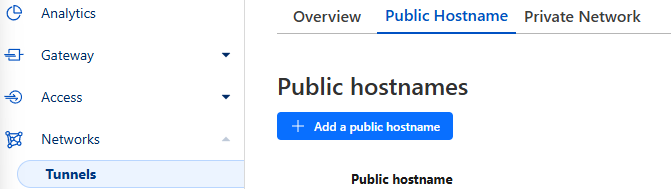

Once your nameservers have been moved to Cloudflare, edit your tunnel, select ‘Public Hostname’ and hit ‘Add a public hostname’.

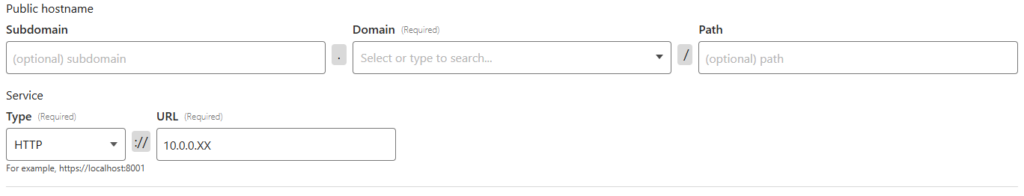

If you want this webserver to be served on ‘www.’, then add that as a subdomain. If not, leave it blank. Select your domain in the dropdown, and then type the local IP address of your server into the URL field below. In the service type dropdown, select ‘HTTP’. Don’t worry, Cloudflare will proxy the website in HTTPS with a Cloudflare certificate.

Step 10:

As I said before, proxying with Cloudflare does break some parts of WordPress. However, this fix for this issue is also an incredible security feature. We will make the WordPress admin panel only accessible from your internal network.

This means that the admin panel won’t be proxied, meaning nothing gets broken, but it also means that the admin panel logon page is not exposed to the internet!

To do this, we will first create a DNS rewrite on your DNS server (usually your home router). You will need to research how to do this for your specific vendor, however the rule should essentially say:

Any DNS requests to ‘yourdomain.com’ get sent to the internal IP address of your web-server.

To test this once it’s in place, open a command prompt or terminal, and use the following command, replacing domain.com with your domain:

Windows: nslookup domain.com

Linux: dig domain.com

This should respond with the internal IP address of your server.

Go back to the admin panel of WordPress and navigate to Settings -> General.

In the ‘WordPress Address’ and ‘Site Address’ boxes type in ‘http://[yourdomain]. Again, Cloudflare will handle the HTTPS, so you must use http.

You should now be able to locally navigate to your domain to use the WordPress admin console at http://[yourdomain]/wp-admin.

You should also be able to navigate to the domain over the internet on a device that does not use the DNS server you just changed.

Step 10:

Due to the issues posed by proxying, we need to install a plugin that will fix an issue caused by editing over HTTP. The ‘XXX plugin fixes these issues.

Install the plugin ‘SSL Insecure Content Fixer‘ and configure the following settings:

Content type: Content

HTTP detection: HTTP_X_FORWARDED_PROTO

This will prevent issues loading images etc.